The International Women’s Day march in Mexico City was one of the largest in the world in recent years. After receding during the pandemic, the traditional mobilisation returned in 2023 stronger than ever—and changed with the times.

There are no words to describe the feeling of marching with 100,000 other women in the streets, in a city where, in certain areas, women risk their lives simply by being in the street. We shouted together, we recognised each other in our shared demands, and, in the euphoria of feeling our power, we identified the “sisterhood of pain” and united in diversity.

This year’s march belonged to the youth, who made up the vast majority of marchers, but it was also intergenerational. Countless numbers of diverse women came together from different parts of the city. A large contingent departed from the Monument to Women Who Struggle, a roundabout on the main avenue where, after protests by indigenous groups, the statue of Christopher Columbus was removed by the city government and the spot renamed by the women’s movement. Now this emblematic urban space is home to a circle of walls painted with the names of the women who fight and have fought for women’s rights and social justice in the country. It is a sign that in Mexico, decolonial feminism is gaining ground.

This year’s march belonged to the youth, who made up the vast majority of marchers, but it was also intergenerational. Countless numbers of diverse women came together from different parts of the city. A large contingent departed from the Monument to Women Who Struggle, a roundabout on the main avenue where, after protests by indigenous groups, the statue of Christopher Columbus was removed by the city government and the spot renamed by the women’s movement. Now this emblematic urban space is home to a circle of walls painted with the names of the women who fight and have fought for women’s rights and social justice in the country. It is a sign that in Mexico, decolonial feminism is gaining ground.

Women retook the urban territory in the city of 20 million with their autonomous use of the first territory—their bodies. They filled Reforma Avenue, the sidewalks and the surrounding streets. They showed the strength not only of those present, but also of those absent—the thousands of disappeared and murdered women in a country that generates more every day.

Teenager Paula Camargo’s face smiles from the palm tree where her photo hangs, with the caption: “2,752 days disappeared.” Marlen Cruz carries a canvas larger than her with the printed photos of her daughter, Janette Tafoya Cruz, a victim of femicide, and Angelica Ambriz Tafoya, her granddaughter that was also kidnapped by the murderer. She denounces government inaction: “The State has done absolutely nothing more than mock our pain.” “I came to the march because all together we form a single voice asking for what may be impossible in this life.” Justice. Through tears, she adds a message for her little granddaughter: “Angelica, wherever you are, I love you with all my soul and you deserve a life filled with love.”

Teenager Paula Camargo’s face smiles from the palm tree where her photo hangs, with the caption: “2,752 days disappeared.” Marlen Cruz carries a canvas larger than her with the printed photos of her daughter, Janette Tafoya Cruz, a victim of femicide, and Angelica Ambriz Tafoya, her granddaughter that was also kidnapped by the murderer. She denounces government inaction: “The State has done absolutely nothing more than mock our pain.” “I came to the march because all together we form a single voice asking for what may be impossible in this life.” Justice. Through tears, she adds a message for her little granddaughter: “Angelica, wherever you are, I love you with all my soul and you deserve a life filled with love.”

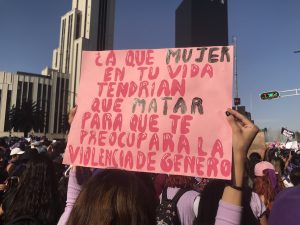

Many women answer the question, “Why are you marching today?” by saying that they march for the women who are afraid to march, who continue to battle trauma, pain, and anger. There are many signs that read: “For my grandmother, for my mother, for my sister, for my daughter, for me, FOR ALL OF US.”

Daniela López explains: “I came because I am literally fed up with the fact that we cannot go out into the streets…I came because many of my relatives were afraid to come out to the march, I came on behalf of my relatives, my friends, my clients (because I’m a hairdresser), my nieces, my goddaughters–for all of those women who did not want to come because they’re scared they won’t make it home again.” Mariana Rodriguez from Toluca says she’s marching for the first time, after just getting out of a violent relationship. She belongs to a group called “It’s not one, it’s all of us.”Behind her marching are groups that fight for menstrual education—they define themselves as “feminist and trans-inclusive” and carry out popular education campaigns throughout the city.

Another sign that pops up frequently in the crowd reads: “Don’t let your privilege cloud your empathy.” A young woman from the UPN Violeta collective of the national university explains, “From my perspective, feminism goes beyond gender–we must seek respect for everyone, but inequality and violence against women is really prevalent.” A young woman from the Good Vibes collective of lesbian and bisexual women marches “because I not only want equality in my paycheck, I want them to stop yelling at me, stop harassing me in the street; I want to feel safe at parties.”

For every woman shouting slogans and marching, there are huge numbers of women who remain invisible. With this physical and moral strength, a sign raised up high reads: “Nothing can stop this herd anymore.”

Mexico’s president has repeatedly branded the critical feminist movement as fi-fi. It is a common patriarchal tactic to divide and weaken women’s movements, by characterizing them as a small faction of capitalist, white, upper-middle class women. Undoubtedly, there are groups with these characteristics that call themselves feminists. But the demonstration in Mexico City on March 8, 2023 refuted the myth of an elitist women’s movement.

Women from all walks of life marched together—students, workers, professionals, journalists (also targeted by violence), straight and lesbian, mothers with babies, older women. Micaela says, “I am a trans, black, Dominican woman who has lived in Mexico for ten years and I’m part of the Frontera collective, a therapeutic collective.” She remembers that she used to come often to the March 8 marches in the city. “My last march was in 2019, but I stopped going to the marches because they were very violent for trans women. There was always a hegemonic, transphobic, institutional, racist feminism that constantly humiliated us, stigmatized us, criminalized us, and in this specific march,my physical integrity was violated. From then on, I stopped attending the marches. But today I return precisely because I realise that in the face of this feminism that denies us and that denies the plurality of trans women—that is, that women come in many forms, that we are black, cis, trans, communitarian, racialised, borderless– and that they deny us in particular, I have to be present, because silence is not an option.”

Women from all walks of life marched together—students, workers, professionals, journalists (also targeted by violence), straight and lesbian, mothers with babies, older women. Micaela says, “I am a trans, black, Dominican woman who has lived in Mexico for ten years and I’m part of the Frontera collective, a therapeutic collective.” She remembers that she used to come often to the March 8 marches in the city. “My last march was in 2019, but I stopped going to the marches because they were very violent for trans women. There was always a hegemonic, transphobic, institutional, racist feminism that constantly humiliated us, stigmatized us, criminalized us, and in this specific march,my physical integrity was violated. From then on, I stopped attending the marches. But today I return precisely because I realise that in the face of this feminism that denies us and that denies the plurality of trans women—that is, that women come in many forms, that we are black, cis, trans, communitarian, racialised, borderless– and that they deny us in particular, I have to be present, because silence is not an option.”

When asked if this year is different, she says that right-wing, transphobic feminism persists, but “there are other groups of women who are inclusive, who have a broader, decolonial vision.” This “expanded vision” opens the way forunexpected encounters. Women protesters give candy to policewomen, many watching the march with smiles as if it were their own, their shields decorated with messages and colorful paint thanks to the creativity of the protesters. The protesters make way for men that are uncertain they can cross the street flooded by the stream of purple. Some men participate openly while others support, report or photograph without incident .

The march expressed joy, sisterhood, strength, and plurality. The only confrontation occurred late at night when the protesters arrived at the seat of the patriarchal state, the National Palace, where some demonstrators attacked the barricades and the police fired tear gas at them. The press highlighted this moment as part of its smear campaign against feminists; however, it was the most peaceful march in years despite the structural violence that women face every day.

isation

isationMarch 8 in the Mexican capital is traditionally a show of strength and convening power for women’s movements. It also offers an opportunity to measure not only the strength but also the evolution and priorities of the movement, according to changing times and contexts. The pandemic marches reflected the health crisis—smaller and marked by masks, frustrations, and repression. In this march, there were changes in ways of organizing and in the demands.

Women marched mostly in smaller groups, not in large contingents. The days of formations of people lining up behind a large banner held up by hierarchical leaders have given way to collectives carrying personal handmade banners, individuals motivated by their own life stories, students and workers who identify with the cause rather than the institutions that brought them together.

In this fluidity of thousands of bodies packed in the street, they meet and care for each other, holding hands in chains, or stretching ribbons to hold on to and not get lost in the crowd. They create paths to get women out who feel overwhelmed, sun-stricken, or just want to leave the march. They organize their own security brigades. They shout the slogan: “The police don’t take care of me, my friends take care of me,” which expresses not only their ability to protect themselves but also a challenge to the patriarchal state—protection doesn’t come from above, it comes from the women by my side.

In this fluidity of thousands of bodies packed in the street, they meet and care for each other, holding hands in chains, or stretching ribbons to hold on to and not get lost in the crowd. They create paths to get women out who feel overwhelmed, sun-stricken, or just want to leave the march. They organize their own security brigades. They shout the slogan: “The police don’t take care of me, my friends take care of me,” which expresses not only their ability to protect themselves but also a challenge to the patriarchal state—protection doesn’t come from above, it comes from the women by my side.

With broad diversity and new generations leading the way, Mexico City’s International Women’s Day march this year revealed a movement that is regenerating and reinventing itself with tons of energy and commitment. Some debate whether this is the fourth or fifth feminist wave, but whatever its place in history, today it felt like a tsunami.