As a global capital, New York City is accustomed to high-level discussions on earth-shaking issues. But something different is happening.

Two events in a single week – the UN Climate Summit and the UN World Conference on Indigenous Peoples along with discussions on new global goals on development and women and girl’s human rights, are rocking even the jaded city. Deeply interrelated, these events raise debates that will determine what kind of a world we live in this generation – or even a few years from now.

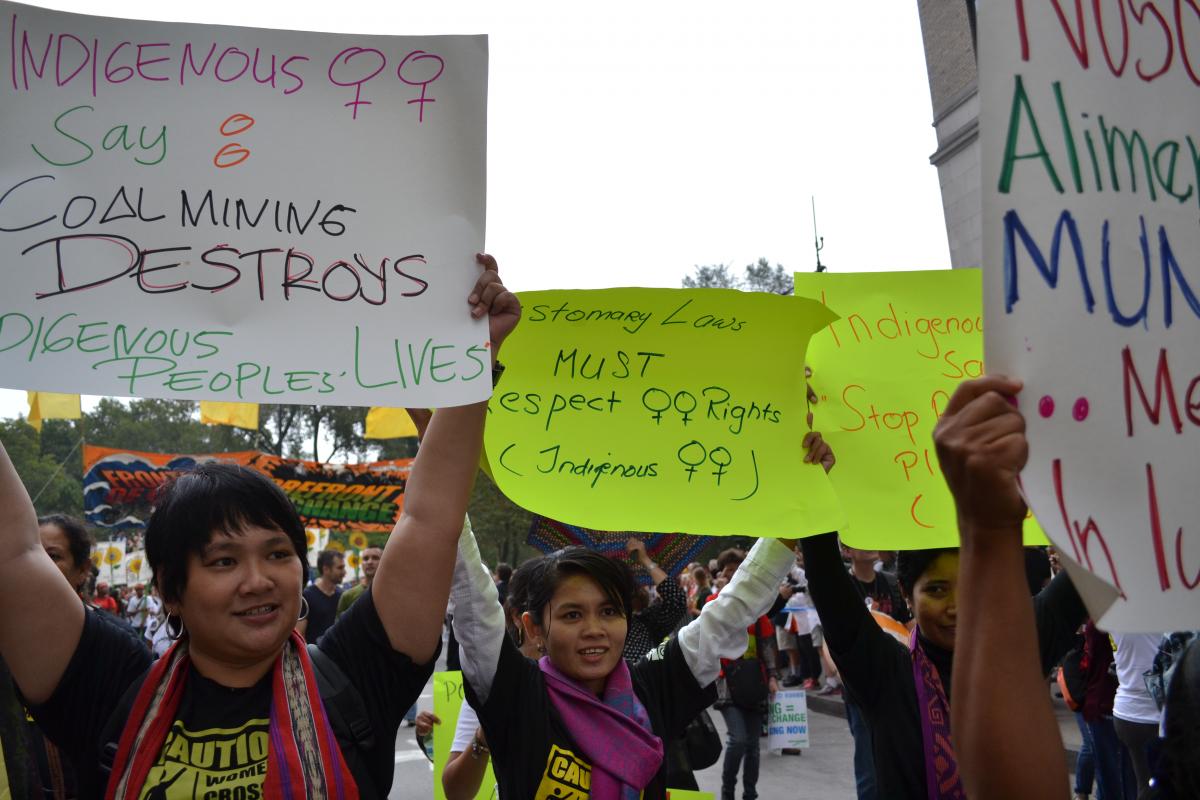

Add to that, the People’s Climate March on 21 September, where more than 310,000 people took part in what’s been deemed “the largest climate march in history,” and we could have what historians call a “defining moment”. It’s not that we shall see big decisions come out of any of this. The wheels of international bureaucracies are slow and creaky, and the differences profound.

Far more important than the official declarations will be the real dispute: Who gets to decide and how?

There are some voices that have been silenced for centuries – in the home, in the community, in governments. These are the voices of indigenous women. Unless these voices gain strength in the discussions and deliberations, no decision – no matter how enlightened it may appear – can be balanced, informed or legitimate.

And we’ll also miss out on some of the most innovative and effective solutions around. Without fanfare and against all odds, indigenous women are developing practices that can be replicated to confront the toughest issues of our day: climate change, inequality, development, democracy and security.

To give some examples: Maria Ricca Llanes is a young, indigenous woman from Cordillera region of the Philippines. She works with a regional alliance of women’s organizations that delivers relief and helps rebuild communities devastated by a series of off-season typhoons linked to global warming.

On the other side of the world, Felicitas Martinez, an indigenous Me’phaa, works to counter poverty and government neglect in her home community in one of Mexico’s poorest regions. She’s a member of the community police, an indigenous law enforcement and justice system that has proved to be far more effective than corrupt government security forces in controlling crime and ensuring justice.

On the other side of the world, Felicitas Martinez, an indigenous Me’phaa, works to counter poverty and government neglect in her home community in one of Mexico’s poorest regions. She’s a member of the community police, an indigenous law enforcement and justice system that has proved to be far more effective than corrupt government security forces in controlling crime and ensuring justice.

Up north, the indigenous women at the forefront of Idle No More, a First Nations movement set off by Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s dismantling of environmental protections, have become headline news as they push back to protect rivers and forests, making important legal gains in reasserting their historic rights.

Just Associates (JASS) has worked with women like Maria and Felicitas throughout the world. Many fight corporations that are polluting or illegally occupying their land. We see disconcerting similarities throughout the world: the mining boom, for example, has set indigenous women up against transnational companies, often backed by governments eager for the foreign investment with total disregard for basic environmental and labor standards.

Many pay a high price for their community activism. In Guatemala, indigenous communities held community consultations and voted to reject large-scale mining projects on their land, as is their right according to international law. Indigenous leader Lolita Chávez, Guatemalan K’iche’, and a group of her sister activists were ambushed on a bus by a group of men armed with machetes and knives. Four of the women were wounded. Lolita also has an arrest warrant out against her for her work in defense of the communities’ right to be heard.

There’s a clash of worldviews here. It’s no coincidence that indigenous territories contain the vast majority of the earth’s remaining natural resources. Indigenous communities have a long tradition of conserving and respecting Mother Earth. And within those communities, women play a key role in transmitting cultural knowledge, adapting to often difficult conditions and maintaining a balance between the environment and human needs.

The rush to exploit those resources as thoroughly and quickly as possible is foreign to them. As one woman from the lush Guna Yala in Panama (Graciela) remarked about developers coming into her islands, “When they see green, all they see is money.”

Indigenous women remind us that it’s time the colour green took back a living connotation. We have to at least balance economic interests with longer-term considerations, and with a healthy respect for other people and other living things.

We’re hearing many opinions, ideas and controverting facts bandied about over the next few days. In the end, it comes down to who is allowed to speak and be heard. Whose voice matters.

Taking into account indigenous women’s voices is not just a question of historical justice after centuries of discrimination, although that’s important. It offers the opportunity to tap a millennia-old source of knowledge that has been constantly evolving. Far from the podiums, in small villages in mountains, lowlands and plains, indigenous women are innovators in developing new solutions to the most pressing needs of today’s world.

They’ve been muted by centuries of racism and sexism, but many courageous indigenous women have travelled to New York this week to speak out.

We can’t afford not to listen.

This article was originally published on openDemocracy.