By Laura Carlsen Km. 148 is a nodal point on the Interamerican Highway that connects…

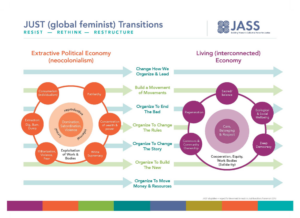

Last April, the EDGE Funders Alliance held its Reorganizing Power for Systems Change conference in Barcelona, providing social movement activists, organizations, and progressive donors an excellent opportunity to discuss strategies for advancing transformative social change through and across our various movement struggles. JASS attended the conference and emerged with a global feminist twist on the framework and accompanying diagram which shaped the dialogue.

The organizers used the Just Transition framework and diagram as a way to engage participants from diverse perspectives in conversation about the deep challenges of the current context and in a joint analysis of the necessary dimensions of systemic change. Developed by Movement Generation through its work with grassroots communities, Just Transition provides a strategic framework to help people envision a model of a regenerative economy – one based on ecological restoration, community resilience, and social equity1 – and it offers a set of broad strategies to enable transition toward that vision and away from the currently dominant extractive economic model. Globally, the extractive economy is based on the concentration of wealth and power, and on the escalating exploitation of resources and human labor which drive land dispossession, violent conflict and genocide, and the massive depletion of the biological and cultural diversity on which our collective survival depends2.

The Just Transition framework, in presenting a holistic model of change, interconnects and offers support to various resistance and human rights struggles. It resonates with the proposals of ‘Buen Vivir,’ [a Latin American and indigenous term for ‘living well’ and in harmony with the living world], feminism(s), and other systemic change philosophies. From JASS’ decades of experience strengthening the collective power and safety of feminist activists and movements in Mesoamerica, Southeast Asia, and Southern Africa, we believe that this framework can contribute to strategic clarity in our work and facilitate dialogues across movements. In the following set of notes, we will look at Just Transition in relation to JASS’ experience and existing conceptual frameworks, and share some of the challenges we see in advancing this model.

How does patriarchy support the extractive economy? Why is gender justice fundamental?

The Just Transition framework recognizes patriarchy as one of the key pillars of the extractive economy3. It is essential, therefore, to deepen our understanding of how patriarchy functions to support this economic model and the resulting impact on society. Patriarchy together with racism and colonialism constitute the interconnected and pre-capitalist structures of domination that are the foundation of the extractive economy. Maintaining power and control over the work, bodies, and sexuality of others, with women representing more than half of the world, has historically been a source of privilege and access to resources – material and symbolic – for those in power (as an example, consider the huge profits generated by the trafficking of women.) One of the clearest examples of how the extractive economy uses patriarchy is the exploitation of women’s domestic and care giving work. Despite sustaining the social structure– satisfying the primary needs of food, health, and hygiene and ensuring basic care for all people – this work is also the most precarious work, given little social value and assigned to women as expectation and obligation.

However, patriarchy is not only promoted by state structures and powerful groups. It is also strongly rooted and normalized in individuals, families, and the social fabric as a whole. It is even present within social movements that often have a culture of male leadership which marginalizes and devalues women. Gender discrimination operates as an invisible4 power that reinforces the low social value of women (and LGBTI community members), the invisibility of their caregiving and domestic work, and their exclusion from decision-making spaces. Patriarchy is a form of domination based on violence. Maintaining the subordination and exploitation of women requires structural violence that kills millions of women every year. The media, churches, and public institutions normalize, justify, and foster this violence, which women also experience in families, communities, social organizations and movements. The use of violence and discrimination against women to thwart their power, voice and freedom is a serious obstacle to a Just Transition.

Gender justice must be an essential element in any change process because only through the transformation of families, communities, movements, and States will we succeed in creating a world not organized on the basis of gender inequality, that is to say, the continued exploitation of women’s bodies and work. Integrating gender justice more fully means

– Prioritizing women’s political and social empowerment and leadership, particularly for those who experience intersecting forms of discrimination (of race, class, sexuality, gender, ethnicity, location, etc.) that prevent their participation on equal terms; We need to ensure that women’s consistently suppressed histories, voices and perspectives can come forward and they can lead. From the perspective of women and those facing multiple oppressions, having safe space, equitable treatment and the recognition of fundamental rights and freedoms, is essential to a just transition.

– Understanding the profound implications of placing care for life at the center, of reorganizing society to prioritize social cohesion and attention to basic needs – including caring for the web of life, creativity, and education for peace. This means ensuring that everyone – not just women – is responsible for domestic and caregiving work; of doing away with gendered roles and the sexual division of labor.

– Involving men, including within our social movements, in questioning and deconstructing the privilege and power afforded by patriarchy and white male supremacy. They must step back, listen to women and all those impacted, and make fundamental changes in behavior and practice. Only in this way can we develop egalitarian relationships and deep democracies.

How do we achieve this transition in a context of closing civic space, political repression and violence against social movements?

Globally, governments join corporations and other non-State interests in using their power to defend the extractive economy, even as its impact endangers their own human survival. In the contexts in which JASS works, we face the challenge of working for systemic change in contexts of deeply corrupt governance structures infiltrated by criminal and private influence and largely closed to citizen dialogue. These shadow powers5 include transnational corporations, drug cartels, or religious fundamentalist groups, seeking to protect and advance their interests. The international human rights framework, designed to protect dissent and activists, is systematically violated and democratic space is increasingly shuttered, thereby weakening civic institutions and citizen participation.

We were inspired by stories of successful organizing we heard about at the EDGE Conference, such as municipal governments led by people from social movements in Catalonia that helped restrain regressive policies, restrictive legal frameworks and excessive corporate power that thwart efforts toward a just transition. Yet in Mesoamerica, organized crime and huge transnational companies exert a rising level of control over formal power structures, making it risky and virtually impossible for movements to occupy institutional spaces. So-called ‘developed countries’ that boast of robust democracies exacerbate the situation because they benefit from and are enriched by the authoritarian regimes of the region, which allow them to more easily impose their economic interests.

In this configuration of power, states use the criminalization of activism, security policy and militarization to repress organized resistance, particularly by movements and communities that directly oppose the extractive economy, and to stop the creation of regenerative alternatives. As we discussed in our workshop with Calla and the Urgent Action Fund during the EDGE Conference, in many regions of the world, attacks and assassinations of human rights defenders and activists are increasing, as is the use of narratives that manipulate beliefs and public opinion to legitimize violence and discrimination and undermine movements.

In its latest report, Front Line denounced the assassinations of 281 human rights defenders in 25 countries in 2016, 49% of whom defended the land, indigenous peoples’ rights, and the environment. In Mesoamerica alone, according to data from the Iniciativa Mesoamericana de Defensoras [Mesoamerican Defenders’ Initiative]6, between 2012 and 2016 at least 42 women defenders were murdered in Mexico and Central America, most of them for defending their territories.

Violence against movements has multiple, and intended, results: it endangers the lives and cohesion of social movements, weakens their strength and collective power through fear, causes internal tensions and conflicts, and steals vital time and energy from advancing agendas of social change. Women activists experience these impacts differently. Women human rights defenders are at greater risk of experiencing sexual violence, being the targets of campaigns to discredit them through stigma and sexist slander, and having their sons and daughters threatened. In addition, in many cases, they face attacks in their immediate surroundings – such as within their families and organizations – for stepping out of gender roles and assuming leadership.

Political violence has greatly eroded the social foundations of movements in many places, while fear and political manipulation make it increasingly difficult to organize new people and communities. That is not to say that society does not continue to be active and outraged in the face of injustices; however, it is not easy for movements to transform that outrage into sustained processes of political participation.

Strengthening social movements to achieve systemic change

In order to achieve a Just Transition faced with these challenges, it is important to review strategies and resources focused on institutions and governments that close democratic space and perpetuate violence, and simultaneously to critically assess our approach to the protection of activists and organizing. To that end, in 2017 JASS in partnership with the Global Fund for Human Rights began a process of collective reflection with a range of grassroots and NGO partners about strategies and tools for both protecting and strengthening movements and activists – so they can continue their vital work for change7. One of the main lessons thus far is that:

We need to redefine protection and security – looking more deeply at gender and power dynamics and learning from approaches to collective safety created by grassroots communities. Even as we continue to need emergency measures and institutional protocols to protect those most at risk (e.g. legal mechanisms, security cameras, ‘panic buttons,’ safe houses), we can learn a great deal from feminist and community based strategies that are both enhancing collective protection and building the resilience of their communities, organizations, and movements to continue their struggle.

Ensuring a Just Transition toward a new economic model requires strong movements that can confront violence while increasing their collective power. We need coherent movements that internally recognize and combat all political practices that are anti-democratic or perpetuate discrimination, and develop the capacity to deal with internal conflict. There is much to learn from the experiences of collective protection that indigenous peoples and women are developing in their communities and from the social and economic alternatives that their movements are developing that defy the logic of capitalism, and in whose heart, exists the potential to create a regenerative economy.

We must also look at the relationships between progressive movements and donors. The EDGE Conference emphasized that fundamentalist and anti-rights groups have enormous resources to advance their strategies, even as social movements working for systemic change have less access to resources even as the precariousness of their work has increased. Having sufficient and sustained resources is necessary for social to movements to grow and gain power. Several ideas emerged at the conference, such as returning to the long-term financing model or using multi-sectoral financing. However, it was also noted that without addressing the power relations, privileges, and inequality that exist among movements and donors we will limit the formation of truly strong and strategic alliances.

The bottom line is that progressive organizations and donors should work together on regenerating and protecting movements, taking into consideration the analysis noted here, in order to increase our collective capacity to activate hope, rebuild the social fabric, and mobilize all of our collective power for the systemic change – the just transition – that our world so desperately needs.

Power – Intersection of arenas and dimensions8

Power is used to gain and maintain control in decision-making processes and as regards resources, and to define who and what matters and has worth. This type of “power over” can be understood if we visualize three particular and interconnected forms, each with its specific actors, impacts, and expressions:

- Visible/formal: The State and formal political power: the laws, rules, authorities, institutions, and processes for decision-making and compliance with and oversight of the rules.

- Hidden/shadow power: Non-State actors (legal + illegal) that influence and control State power, political agendas, and policies. Operating behind the scenes, hidden power excludes and delegitimizes the concerns of less-powerful groups by creating political narratives (disinformation, preventing information from being made public) and using indirect or direct threats and violence to maintain power.

- Invisible power: The power of beliefs, ideology, social norms, and culture to influence people’s worldviews, self-awareness, and values, as well as the acceptance of what is considered to be normal and correct. Some cultural, religious, and political actors also manipulate beliefs and narratives to legitimize certain ideas and behaviors while delegitimizing and even demonizing others.

- The Tanks and Banks for Cooperation and Care. Movement Generation, p. 15.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- Ibid., p. 7.

- See at the end a synthesis of the power framework we in JASS utilize for contextual analysis

- Ibid.

- Coordination of networks and organizations in Mexico and Central America founded by JASS and other organizations that brings together nearly 800 women defenders from different social movements and provides strategies for protecting at-risk activists (system for recording attacks, three shelters, urgent actions, emergency funds, etc.). For more information, see:http://im-defensoras.org/es/.

- Video with some of the reflections that emerged from the meeting: http://globalhumanrights.org/activists-need-new-tools-to-protect-themselves/.

- To learn about JASS’ framework of power, please see ‘A New Fabric of Power, Peoples, and Policy,’ JASS, https://justassociates.org/es/publicaciones/nuevo-tejido-poder-pueblos-politica-guia-accion-incidencia-participacion-ciudadana.

Please visit Edge Funders for the original document.