A few weeks ago, I attended a discussion on Land Grabbing in Zimbabwe. As a Zimbabwean who grew up on a farm, I assumed I knew everything there was to know about this issue. Yet, like most people, I had understood this process from a racial, class & historical perspective because the debates around this issue focus almost entirely on the infamous brutality of the “fast track” resettlement program in 2000.

However, after this discussion, I realized that there was an untold story to the land issue in Zimbabwe – an untold story that has always existed even before colonization. This is the story of women – my grandmothers, aunts and sisters who I grew up watching primarily work on this land – but who have been denied a chapter to this story. Since the debates around the land reform are largely constructed around race and economic growth, gender issues are either ignored or unanalyzed. So, as I pondered away in thought, I was led to ask, “If women play a central role in farming, why is their access to land minimal?”

It is clear that other issues are at play here. Despite women’s central role in farming, their subordinate position mediated by cultural and social expectations often inhibits their ability to own land. In a culture that privileges men, it is no surprise that women’s entitlement to land and home comes through marriage. This immediately draws me to memories of my grandmother working the rural field to produce crops and vegetables to feed her family while my grandfather worked in the city. I even remember the few times where my grandmother tried albeit futilely to show me how to hold and use garden hoe every time I went to visit her because it was viewed as an important trait to have to be considered “marriage” material. Therefore, not only are women expected to play certain roles in order to be considered “worthy” of marriage, but these same roles are used to further entrench their position. In this context, marriage then takes on deeper and symbolic implications for women’s access to resources i.e. land.

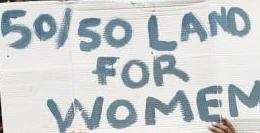

If women’s access to land is mediated through male power and control, how then do we address their plight? Clearly, simply advocating for a land reform program is not enough because even though Zimbabwe has been in the process of redistributing land (although problematic), it is estimated that only 20% of women have received land. While the current land reform, divided into two parts A1 and A2 shows women as significant beneficiaries in the former, it is still not clear whether these are just women who have been able to capitalize on their use of social networks and political party affiliations to acquire land. In any case, the need to give women more access to land remains an extremely important and controversial issue in Zimbabwe.

It is thus important to create a land reform program that addresses the inequalities that women suffer. Yet, this is not an easy task because the very act of distributing more land to women implies challenging the spaces were men are in control. In this patriarchal culture, men’s power is derived from their ability to not only control resources, but also, who has access to them. As a result, fighting for equal rights for women often contradicts their main cultural identities as married women, mothers, etc, while threatening men’s identity and power.

Consequently, there is a conflict between cultural practices, attitudes and laws that constrict women’s role and individual modern rights that seek to broaden this role. Hopefully the new Referendum will provide a changing landscape for women in Zimbabwe to challenge programs and laws that either discriminate against them or simply ignore them as citizens worthy of the same resources that the government declares belongs to its “citizens”. With the help of organizations such as Women and Land Lobby Group (WLLG), women’s plight when it comes to land will continue to be put on the table and eventually be included in the narrative for land rights in Zimbabwe.

Photo credit: Actionaid

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 6 months | YouTube - to provide bandwidth estimations. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | Google Analytics - Used to distinguish users. |

| _gat_gtag | 1 minute | Google Analytics - Used to throttle request rate for analytics |

| _gid | 24 Hours | Google Analytics - Used to distinguish users. |

| VUID | 2 years | Vimeo - Statistics - to store the user's usage history |

| YSC | session | YouTube - to Store and track interaction. |

Adelaide Mazwarira

Adelaide Mazwarira is a Zimbabwean feminist writer and creative storyteller – something she brings to many of JASS’ communications, publications, outreach and fundraising efforts. Adelaide currently works as the Communications Manager at JASS and is based in South Africa.

Her passion for feminisms and social justice grew from a young age which she has channeled in work with domestic violence survivors and research assistantships on violence against women and children. In her free time, Adelaide catches up on Law and Order Special Victims Unit, and her scrapbooking, and writings.

Tasha Pick (SOAS): Tasha is a queer feminist researcher based in London. Their work is situated across academic, creative and community spaces. They hold a Masters in Gender Studies from SOAS, University of London, and are about to begin a PhD exploring the connections between oceans, queer time and climate crisis. Over the past year, they have been working in public engagement at Queen Mary, University of London. Their most recent collaboration brought together East London migrant support organisations with local artists, writers and performers. Their work seeks to explore the radical imagination, the capacity to imagine and enact alternative futures, as a form of resistance to unliveable worlds.

Ronald Wesso lives in Johannesburg, South Africa. He works as a popular educator and freelance researcher at Bentec, a research and training consultancy supporting movements for social justice around natural resources, gender and labour. Ronald has experience working with labour, land, community and feminist movements. He has written widely on these matters, including the recent popular education manual ‘Behind the Scenes of Extractives: Money, Power and Community Resistance‘ published by the Count Me In! Consortium.

Rosa is a poet, artist, & activist of Mayan K’iche Kaqchiquel origin who has studied social sciences, cultural management and cinema and audiovisual performances. Rosa works enthusiastically and passionately with women and movements in Guatemala as the program coordinator with JASS. She has more than 15 years of experience working in community art processes and organizations for the Mayan movement. Rosa enjoys co-creating with other artists, feeling nature, drinking tea, enjoying music, and dancing a lot. Being aware of the history of her people and healing the history of her body, fills rosa with the energy necessary to work and fight with passion and in collective, for a bountiful life with other women, communities, and peoples.

Patricia adalah seorang perempuan Guatemala tulen dan feminis dengan gelar di bidang Antropologi Sosial. Patricia telah menulis artikel dan menerbitkan beberapa karya yang berkaitan dengan konteks regional, pembangunan perdamaian dan kontribusi perempuan dalam proses-proses ini, serta merancang dan memfasilitasi proses pelatihan, dengan penekanan dalam beberapa tahun terakhir pada Pendidikan Populer Feminis. Patricia menjabat sebagai Direktur Regional JASS Mesoamerika di mana ia berfokus pada produksi pengetahuan dan merupakan bagian dari Tim Kepemimpinan global JASS.

Alexa Bradley sudah bekerja sebagai organisator, fasilitator, ahli strategi organisasi, dan pendidik populer selama lebih dari 25 tahun. Dia mendirikan dan ikut memimpin Milwaukee Water Commons, membantu membentuk Great Lakes Commons, menjadi mitra senior di Grassroots Policy Project dan On the Commons, menjadi anggota dewan di Windcall, dan ikut memimpin Minnesota Alliance for Progressive Action. Saat ini, Alexa adalah Direktur Program JASS.

Tamara adalah seorang aktivis lingkungan yang berfokus pada isu kesetaraan, akses, dan komunitas. Dia mengembangkan inisiatif pengembangan kapasitas dan menciptakan kampanye multimedia untuk menghapus privilese dan meningkatkan peluang bagi populasi rentan untuk mengakses udara yang sehat, energi bersih, dan ekonomi bebas racun di tingkat lokal, regional, dan nasional. Toles O’Laughlin adalah seorang pemimpin yang memiliki banyak keahlian, seorang kolaborator, individu yang kaya akan sumber daya, dan seorang ‘konektor’. Beliau adalah Presiden dan CEO Asosiasi Pemberi Hibah Lingkungan. Sebelumnya, Toles O’Laughlin menjabat sebagai Direktur Amerika Utara di 350.org dan 350 Action, dan memimpin Jaringan Kesehatan Lingkungan Maryland, yang berbasis di Baltimore.

Phumi Mtetwa adalah seorang aktivis yang bekerja di bidang kesetaraan dan keadilan ekonomi, gender, dan LGBTI. Ia memiliki banyak pengalaman bekerja dalam konteks internasional dan regional, khususnya di Afrika Selatan dan Amerika Latin. Sebagai Direktur Regional JASS untuk Afrika Selatan, ia memiliki komitmen dan fokus pada landasan politik Pendidikan Populer Feminis, mengaitkan perjuangan di seluruh wilayah serta memajukan strategi perubahan yang menjadi kunci di saat-saat genting.

Dr. Awino Okech adalah Associate Professor di bidang Sosiologi Politik di SOAS, University of London di mana ia mengajar di Departemen Politik dan Studi Internasional. Dia juga merupakan anggota dewan editorial Human Sciences Research Council, Dewan Pengawas SOAS University of London, dan menjabat sebagai Associate Director Equity and Accountability. Karya-karyanya didasarkan pada pemikiran feminis Afrika, queer, dan internasionalis kulit hitam sebagai kerangka kerja utama untuk menyoal kekuasaan dan keadilan. Awino terus bekerja dengan dan mendukung berbagai dukungan gerakan feminis internasional dan Afrika serta organisasi multilateral dalam proyek-proyek yang berada di persimpangan antara gender dan keamanan serta masalah pengembangan organisasi yang lebih luas.

Tarso Luís Ramos telah menjadi peneliti dan oposisi kubu sayap kanan AS selama lebih dari 25 tahun. Sebelum bergabung dengan PRA pada tahun 2006, Ramos menjabat sebagai direktur pendiri program keadilan rasial di Western States Center, dan mengekspos serta menantang kampanye anti-lingkungan perusahaan sebagai direktur Wise Use Public Exposure Project. Ramos baru-baru ini menjabat sebagai aktivis di Barnard Center for the Study of Women dan merupakan Rockwood Leadership Institute National Yearlong Fellow untuk tahun 2017–2018.

Sohela Nazneen adalah seorang Fellow yang berbasis di klaster Tata Kelola Pemerintahan, memimpin penelitian IDS tentang Gender dan Politik dan memimpin program MA unggulan IDS di bidang Gender dan Pembangunan. Kerja-kerja Sohela berfokus pada pemberdayaan perempuan, gerakan feminis, dan daya tanggap negara terhadap kebijakan kesetaraan gender di Asia Selatan, sub-Sahara Afrika, dan Timteng. Dia telah menerbitkan karya-karyanya secara luas tentang isu-isu ini, termasuk di World Development, Development Policy Review, Gender and Development dan jurnal-jurnal lainnya. Sohela telah bekerja sebagai konsultan untuk SDC, UNWomen, UNDP, Irish Aid, The MacArthur Foundation, dan lembaga-lembaga lainnya.

Zeph adalah seorang aktivis hak asasi manusia dan keadilan lingkungan/iklim di Filipina, feminis, ahli komunikasi, ahli strategi, dan pendidik politik populer yang bekerja dengan berbagai jaringan di Asia Tenggara, terutama jaringan perempuan pedesaan dan masyarakat adat serta komunitas LGBTQ untuk membela tanah, air, wilayah, dan hak-hak mereka. Zeph memimpin proses perumusan strategi tim JASS Asia Tenggara secara keseluruhan sebagai Direktur Regional.

EJ (nama panggilan populernya) telah aktif dalam gerakan feminis dan keadilan sosial di negaranya, benua Afrika, dan secara global. Dia memulai karir pengembangannya dengan Women’s Action Group. Sejak saat itu, EJ menjadi salah satu pendiri Majelis Konstitusi Nasional Zimbabwe, bekerja di Pan-African Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF), menjadi bagian dari Feminist Leadership Institute yang pertama kali diselenggarakan di Center for Women’s Global Leadership di Rutgers University, menjabat sebagai Direktur Global untuk Hak-Hak Perempuan di ActionAid’s International, dan juga sebagai Associate Country Director Oxfam-Canada di Zimbabwe. Sejak tahun 2014, Everjoice menjabat sebagai Direktur Program dan Penjangkauan Global ActionAid International.

Ipsita adalah seorang artivist (aktivis-seniman) feminis muda dan peneliti dari India. Kerja-kerja Ipsita fokus pada topik persimpangan antara gender, pendidikan, dan aktivisme orang muda. Ia sangat percaya dengan komunikasi berbasis harapan (hope-based) dan memiliki ketertarikan dengan ragam emosi manusia yang menggambarkan empati, kebaikan, serta perspektif kemanusiaan bersama.

Ipsita is a young feminist artivist and researcher from India. She works on the intersections of gender, education, and youth activism. She is a strong believer in hope-based communications and loves to capture various human emotions invoking empathy, kindness & shared humanitarian worldview.

Sonia Corrêa adalah seorang research associate di Asosiasi Interdisipliner Brasil untuk AIDS (ABIA), Rio de Janeiro. Sejak tahun 2002, ia telah menjadi salah satu ketua Sexuality Policy Watch (SPW), sebuah forum global yang terdiri dari para peneliti dan aktivis yang terlibat dalam analisis tren global dalam kebijakan dan politik yang berkaitan dengan seksualitas. Baru-baru ini, ia telah menyunting dua koleksi studi tentang “Politik Anti-gender di Amerika Latin”. Ia pernah mengajar di institusi akademik seperti Colegio de México dan Departemen Studi Gender di London School of Economics. Ia memiliki gelar sarjana arsitektur dan gelar pascasarjana di bidang antropologi.

Crystal Simeoni is a Pan-African feminist activist and Director of Nawi – the Afrifem Macroeconomics Collective (The Nawi Collective). She works at the intersection of the technical and the colloquial, of critique and imagination, of knowledge and practice, of language and of the creation of community. She curates the work of the Nawi collective who, in community with other African feminists and organizations, work on analysing, influencing and reimagining macro level economic policies and narratives. Before Nawi, Crystal was head of Advocacy with a focus on Economic Justice at FEMNET, and the Policy Lead for the Tax and the International Financial Architecture pillar at TJN-A before that. She is also currently an Atlantic Fellow for Social and Economic Equity at the London School of Economics. In her understanding, in her critique and her imagining of a different way, her work is always at the service of life.

Raisa adalah Manajer – Program dan Inovasi di CREA. Raisa terlibat secara erat dalam kerja-kerja CREA sebagai bagian dari konsorsium Count Me In! (CMI!), menantang agenda kriminalisasi, dan inisiatif CREA tentang feminist faultiness. Selama lebih dari 10 tahun, Raisa telah bekerja bersama badan-badan intervensi berbasis hak; mulai dari hak-hak orang dengan HIV/AIDS, hak-hak anak, keadilan gender, dan partisipasi politik kaum muda. Kerja-kerjanya meliputi implementasi program, pengembangan kebijakan, pengembangan jaringan, dan penelitian. Ia memiliki gelar M.A. di bidang Pekerjaan Sosial dari Tata Institute of Social Sciences, dan M.A. di bidang Gender dan Pembangunan dari Institute of Development Studies.

Sonia Corrêa adalah seorang research associate di Asosiasi Interdisipliner Brasil untuk AIDS (ABIA), Rio de Janeiro. Sejak tahun 2002, ia telah menjadi salah satu ketua Sexuality Policy Watch (SPW), sebuah forum global yang terdiri dari para peneliti dan aktivis yang terlibat dalam analisis tren global dalam kebijakan dan politik yang berkaitan dengan seksualitas. Baru-baru ini, ia telah menyunting dua koleksi studi tentang “Politik Anti-gender di Amerika Latin”. Ia pernah mengajar di institusi akademik seperti Colegio de México dan Departemen Studi Gender di London School of Economics. Ia memiliki gelar sarjana arsitektur dan gelar pascasarjana di bidang antropologi.

Shereen adalah seorang feminis, aktivis, pendidik populer, akademisi, dan Direktur Eksekutif JASS sejak tahun 2020. Kerja-kerja Shereen didasarkan pada keterlibatannya dengan perempuan dalam serikat pekerja, gerakan sosial, dan organisasi berbasis masyarakat. Shereen telah menerbitkan banyak tulisan tentang feminisme, gerakan perempuan, dan pengorganisasian gerakan sosial di berbagai jurnal, mulai dari jurnal-jurnal Afrika Selatan hingga jurnal-jurnal internasional.

Sonia Corrêa is a research associate at the Brazilian Interdisciplinary Association for AIDS, in Rio de Janeiro. Since 2002, she has been a co-chair of Sexuality Policy Watch (SPW), a global forum comprised of researchers and activists engaged in the analyses of global trends in sexuality related policy and politics. Recently, she has edited two collections of studies on “Anti-gender Politics in Latin America”. She has taught at academic institutions such as the Colegio de México and the London School of Economics’ Department of Gender Studies. Since the late 1970s she has been involved in research and advocacy on gender equality, sexuality, health and human rights, closely following the United Nations negotiations on women’s rights and sexual and reproductive rights. She has a degree in architecture, with a postgraduate degree in anthropology.

Alexa Bradley has worked as an organizer, facilitator, organizational strategist and popular educator for over 25 years. She founded and co-directed Milwaukee Water Commons, helped form Great Lakes Commons, was a senior partner at the Grassroots Policy Project and On the Commons, sat on the board for Windcall and co-directed the Minnesota Alliance for Progressive Action. Currently, Alexa is JASS’ Programme Director.

Phumi Mtetwa is an activist working on issues of economic, gender and LGBTI equality and justice. She has a wealth of experience having worked in international and regional contexts particularly, Southern Africa and Latin America. As Regional Director for JASS Southern Africa, she continues her commitments to the political underpinnings of Feminist Popular Education, interlinking struggles across borders as well as advancing change strategies key for the conjuncture.

Zeph is a Filipina human-rights and environmental/climate justice activist, feminist, communicator, strategist, and political popular educator working with diverse networks in Southeast Asia, particularly rural and indigenous women and LGBTQ community in defense of land, water, territories, and rights. Zeph leads the JASS Southeast Asia team’s overall strategy direction as Regional Director.

Patricia is a proud Guatemalan woman, feminist, with a degree in Social Anthropology. Patricia has written articles and published several works related to regional contexts, the construction of peace and the contribution of women to these processes, as well as designed and facilitated training processes, with emphasis in recent years on Feminist Popular Education. Patricia serves as the Regional Director of JASS Mesoamerica where she focuses on knowledge production and is part of the JASS global Leadership Team.

Tamara is an environmentalist focused on equity, access, and community. She develops capacity building initiatives and creates multimedia campaigns to dismantle privilege and increase opportunities for vulnerable populations to access healthy air, clean energy, and a toxic free economy at the local, regional, and national level. Toles O’Laughlin is a multi-hyphenate leader, a co worker, resource and connector. She is the President and CEO of the Environmental Grantmakers Association. Previously, Toles O’Laughlin was North America Director at 350.org and 350 Action, and led the Maryland Environmental Health Network, based in Baltimore.

Dr. Sohela Nazneen is a Fellow based in the Governance cluster, leads IDS’ research on Gender and Politics and convenes IDS flagship MA in Gender and Development. Sohela’s work focuses on women’s empowerment, feminist movements and state responsiveness to gender equality policies in South Asia, sub Saharan Africa and MENA. She has published widely on these issues, including in World Development, Development Policy Review, Gender and Development and other journals. Sohela has worked as a consultant for SDC, UNWomen, UNDP, Irish Aid, The MacArthur Foundation and other agencies.

Tarso Luís Ramos has been researching and challenging the U.S. right wing for more than 25 years. Before joining Political Research Associates (PRA) in 2006, Ramos served as founding director of Western States Center’s racial justice program, and exposed and challenged corporate anti-environmental campaigns as director of the Wise Use Public Exposure Project. Ramos recently served as an activist in residence at the Barnard Center for the Study of Women and a Rockwood Leadership Institute National Yearlong Fellow for 2017–2018.

Raisa is the Manager – Programs and Innovation at CREA. Her primary area of engagement is with CREA’s work as a part of the Count Me In! (CMI!) consortium, challenging the criminalization agenda, and CREA’s initiative on feminist faultiness. For over 10 years Raisa has been working with rights based interventions on HIV/AIDS, child rights, gender justice and political participation of young people. Her work has included program implementation, policy building, network development, and research. She holds a M.A in Social Work from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, and an M.A in Gender and Development from the Institute of Development Studies.

Dr. Awino Okech is Associate Professor in Political Sociology at SOAS, University of London where she teaches in the Department of Politics and International Studies. She is also a member of the Human Sciences Research Council editorial board, the Board of Trustees of SOAS University of London, and serves as Associate Director Equity and Accountability. Her work is grounded in African feminist, queer, and Black internationalist thought as central frameworks for thinking about power and justice. Awino continues to work with and support a range of international and African feminist movement support and multilateral organizations on projects that sit at the intersection of gender and security as well as broader organizational development concerns.

EJ (as she is popularly known) has been active in feminist and social justice movements in her country, the African continent and globally. She started her development career with Women’s Action Group. Since then EJ has been one of the founders of the Zimbabwe National Constitutional Assembly, has worked in the Pan-African Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF), was part of the first Feminist Leadership Institute held at the Center for Women’s Global Leadership at Rutgers University, served as ActionAid’s International’s Global head of Women’s Rights, as well as Oxfam-Canada’s Associate Country Director in Zimbabwe. Since 2014, Everjoice has been ActionAid International’s Director for Programs and Global Engagement.

Shereen is a Zimbabwean feminist, activist, popular educator, academic and JASS Executive Director since 2020. Shereen’s work is grounded in her engagement with women in trade unions, social movements, and community-based organizations. Shereen has published widely on feminism, women’s movements, and social movement organizing in journals in South Africa and internationally.

JASS equips women activists with the skills and strategies they need to organize others and challenge violence and injustice in politics, in their communities, at work or at home. To date, we have trained more than 3,000 women to lead in social movements and bring fresh ideas and strategies back to their communities, where they mobilize many more.

Onyeka Nwabunnia is a African feminist Researcher and writer with 4 years of experience working in the non-profit sector focused on social policy, gender, and international development. She holds a Masters in Gender Studies and Law from SOAS University of London and a BA in Political Science and African Studies from Colgate University. Onyeka currently works as a Research Officer for the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development in Liberia. Onyeka is the founder of the Blog Griotte, hosted on the feminist knowledge sharing platform The Only Space (TOS). As a feminist, Onyeka is driven by questions concerning how we create knowledge and understand the world.

Collective power is our greatest resource for upending inequality. Building inclusive networks across many divides not only leverages this power for social and political change, but also provides the basis for the collective safety women activists need when challenging the status quo. JASS has catalyzed 8 powerful cross-issue networks and fostered collaboration among 450+ organizations to work together from a feminist perspective.

JASS leverages international networks and allies to advocate and influence the thinking and decisions of governments, donors, institutions, NGOs, and the international human rights community. We have hosted over 100 convenings with academics, civil society organizations, and policy makers, centering the voices and specific concerns of women activists and human rights defenders, and advancing the support for gender equality and feminist movement strategies.

When women speak out and offer leadership, their voices are often dismissed or silenced. JASS turns up the volume on women’s voices by providing greater access to the tools and platforms women need to broadcast their truth and build support for their agendas. Through community radio, social media, hosted political dialogues, engagement with journalists and other communications strategies, we are making sure that women’s stories of change, innovations and feminist perspectives shape the narratives about what’s wrong, what’s needed, and what we are doing about it.

JASS is dedicated to bridging theory and practice and ensuring that the knowledge of grassroots women and activists helps to shape ideas, policies, and practice. We document insights from frontline change processes and multiply their reach and impact in the form of analyses, case studies, toolkits, and other practical resources. The knowledge we produce is widely used by activists and their allies and is influential in the field of international human rights and development.