Ask a roomful of people to stand up if any of them have ever experienced violence personally or know of a woman who has experienced violence. They’ll all stand. Ask this same group if they or the women they’re thinking about have ever experienced justice—what justice tastes like, what it feels like and almost every single woman in the room will sit down.

When activist, Ananda* of the One in Nine Campaign led this exercise at a recent workshop in which I took part along with over thirty activists from all over the world, every single person in the room (including the two men) stood up for the first question. The second question garnered a slightly more interesting response: two people were left standing, one was a white woman from Canada and the other was a land rights activist from just outside Johannesburg, South Africa. I didn’t get to ask either of these women why they kept standing, and the circumstances of the cases they were thinking of but it got me thinking.

We talk about justice all the time as feminists, but what do we actually mean by it? How do we even begin to imagine what justice looks like?

We’ve fought for laws. As of 2013, Zimbabwe “[has a] (new) constitution[s] which generally [has] good frameworks to promote and protect women’s rights” (Everjoice Win, Between Jesus, the Generals and the Invisibles, 2013) but this has not stopped 1 in 3 Zimbabwean women from experiencing physical and/or sexual violence. South Africa has one of the world’s most progressive constitutions that grants full marriage equality and protection to LGBTI citizens and yet there have been over 30 reported murders of lesbians in the last fifteen years. A lot of our struggles for justice take place at a high policy level: we go to the United Nations; we leverage conventions like CEDAW (The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women) and craft protocols on this, that and the other. These strategies are powerful and critical to our feminist movements. But they have their place, and in isolation, disconnected from movements of women and men working together to create alternatives, they aren’t going to take us where we need to go.

For me, I’m asking myself, what does justice look like in my body (which is coded as ‘female’)? What does it look like when I navigate my sexuality within my largely conservative family and communities? What does it look like in our churches? What does it look like when we negotiate condom use with intimate partners? What does it look like when a woman walks down the street at the end of her day and gets heckled by a group of hwindis (minibus taxi drivers), and instead of speaking up and telling them off, she swallows her words and pulls into herself, walks a little quicker and tries to quash the fear churning in her stomach because we all know what ‘happens’ to women on dark streets? More than that, we know what ‘happens’ to women who walk on streets in broad daylight.

Unless we’re ready to confront and define justice as it cuts across every part of our lives and every fragment of our identities so that we can live in dignity, free from even the threat of violence and discrimination, to the fullest of our ability, capacity and desires—then we’re never going to achieve it, not really. And unless women, those on the very frontlines of struggles for gender justice, are right at the table, dreaming up alternatives and crafting a different way to imagine a ‘just’ world then nothing’s going to change. We can make all the laws and policies we want; we can spend all day picketing on the streets; we can spend our nights praying on our knees for some god to make things better—but it won’t matter.

C-A-U-T-I-O-N: Feminist justice is NOT comfort food…

I’ve looked askance at the recent (but not entirely new) efforts to re-brand feminism, package it in ever shinier, glossier trappings that are more palatable and comforting. It’s the kind of feminism a small and privileged elite can swallow with a cup of tea every morning and never have to think about for the rest of the day.

It takes multiple forms like a mythological chimera—it might be a well-known fashion magazine notorious for its overwhelming whiteness and heavy-handed airbrushing that doesn’t do much to promote body diversity claiming to be “deeply feminist” or it might be a recently-launched global solidarity campaign helmed by the U.N., #HeforShe, that posits that one of the biggest reasons to care about gender equality and women’s rights is because of how much patriarchy hurts men. Now while it is true that patriarchy hurts everyone, putting men at the centre of the conversation isn’t going to help the feminist cause. Why? Because men have been at the centre of the conversation for centuries and we can all see how well that’s worked out for us. A fact someone ought to tell Iceland’s foreign minister, Gunnar Bragi Sveinsson, who just announced that his country (along with Suriname) would be hosting a “Barbershop” conference in January 2015 to bring “men and boys” together to talk about gender equality, particularly violence against women in a “positive way.”

I’m sure I don’t have to say it but I will anyway: any conversation about inequality that deliberately excludes the voices of those most affected is an incredible waste of valuable time, energy and resources.

The first thing to realise is that these trends aren’t coming out of nowhere—backlash takes multiple forms and this is just one of its more insidious and sometimes less obvious one. After all, what better way to demobilise feminist movements for transformative change and genuine gender justice than co-opt the political term ‘feminism’ and co-opt feminist spaces so that some people can feel more ‘welcome’.

There has always been and there will always be a push from the mainstream and whoever defines it, usually white men, to make feminism less scary. Less thorny. Less messy. Less challenging. And far less demanding on all of us in forcing us to question ourselves and our privileges—whether they be of racial, gender or sexual identity; social standing, location or class.

Any time we hear that message it should rouse a red alert alarm in our heads because guess what? Feminism was never meant to be this easy. Feminism isn’t always about leaving us with a nice warm feeling in the pit of our bellies (although that’s great, and in a violent and frankly terrifying world, it’s cool to feel good about something).

It’s on me to deal with my privileges, to confront and unpack them just as it’s on you to grapple with yours. We can’t allow hurt feelings to get in the way of that individual and collective project.

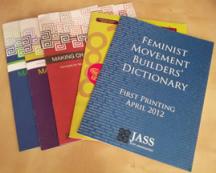

I’d like to go back to JASS’ most recognisable rallying cry because it’s always resonated with me but it didn’t really hit me until this latest onslaught on feminism why.

Caution, women crossing the line. It’s a warning sign. It’s a foghorn blaring and it’s telling the world that we’re coming. We are going to transgress the norms of what it means to be ‘woman’ and blow up your binaries, we are going to break your institutions and rules and build new ones, we’re going to carve out the meaning of justice for ourselves—and if you won’t give it to us, we’ll just have to take it. You are probably not going to like this and you’re probably going to try to stop us, discourage us, beat us back into the tiniest box you can find where we’ll sit down and keep our mouths closed like ‘good women’—

But we will keep coming.

*Ananda requested that her name be withheld.